Moving along the El Camino Real1, I made my visit to Mission San Jose last month. I naturally assumed by its name that it was located somewhere in San Jose. Interestingly enough, it’s actually located in the city of Fremont!

Getting to Mission San Jose

Unless you already live in or nearby Fremont, I think the best way to get to the city is by car or BART. I chose to ride the BART train, which conveniently brings you to Fremont station.

Once you arrive, exit to the East Plaza where there’s a bus bay for AC Transit buses:

I took Bus 211, which takes you straight to the Old Mission. The distance from the BART station to the Mission is only about a 10 minute drive, but it takes about 20 minutes by bus. That being said, it’s a pleasant ride through the city. You’ll pass by a high school and street named after the Mission, along with mission-style buildings:

First Impressions

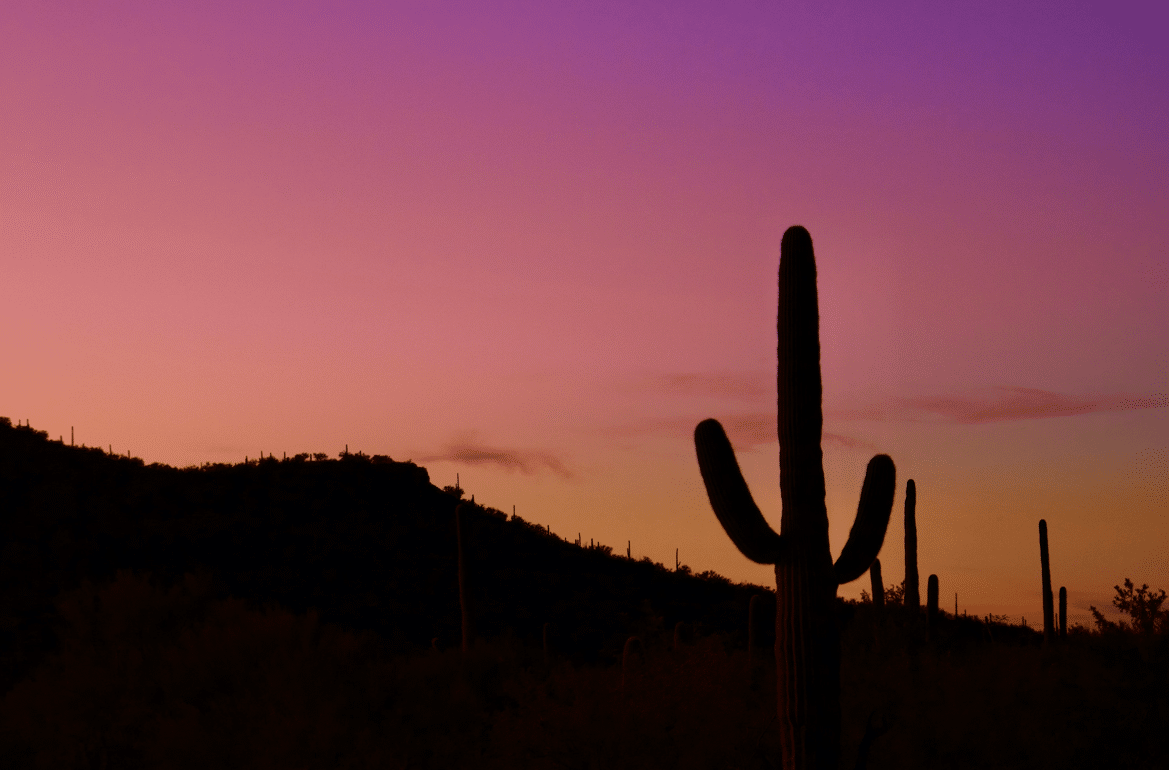

As Google Maps advised, I got off at Mission & Washington Blvd. and faced up close the Mission I had only seen in pictures. I have to say, it was so much larger than I had expected! I think it’s actually bigger than Mission Dolores and Mission Santa Clara. Facing it up close, Mission San José was a giant, white block of a chapel, uniquely imposing in its simple grandeur.

The Mission was right on a busy road and atop an elevated area, below regional parks and mountains like Mission Peak. Unlike Mission Dolores and Mission Santa Clara, it also had a long, semi-circle flight of stairs:

It was large also in terms of its extent. Per this map stationed at the front, the Mission Church was part of a complex of buildings that included a separate visitor’s center called, “Pilgrim Center,” a museum, cemetery, St. Joseph Main Church, Dream Garden, St. Joseph School, and more:

With so many spots to check out, I wasn’t sure where to head to first. But since my main focus was the Old Mission, I decided to go where the “Mission San Jose” signage was pointing to: the Pilgrim Center.

Pilgrim Center (Visitor’s Center & Gift Shop)

Walking up the ramp and passing by adorable (and maybe historic?) benches, I arrived at the entrance to the Pilgrim Center.

The Diocesan Shrine/Mission and Communications Coordinator, Donna, shared with me that the visitor’s center at Mission San José is called, “Pilgrim’s Center,” because it was dedicated to the first pilgrims, the Holy Family of Joseph, Mary, and baby Jesus. And as the site is also visited by practicing Catholics who visit for religious reasons, the Mission Museum is arranged so that people of faith could walk through and arrive in the heart of the museum, the Chapel of Healing, as part of their pilgrimage visit.

When I pushed open the wooden door, I was immediately met with this view of historical artifacts, timeline, and an informational video playing in the background:

On the left-hand side was the entryway to the Gift Shop:

There were souvenirs like magnets, keychains, crosses, postcards, and more. (Some items are even available for purchase online! Link to Mission San Jose Online Gift-Shop: https://oldmissionsanjose.square.site/)

On the right was the front area for purchasing admissions tickets and entering the Museum:

And while I didn’t have to for Mission Dolores, I needed to check in my backpack before entering the Museum. (I was allowed to take my small bag with me, though.) The staff at the front also handed me this high-quality pamphlet:

Admission for one adult was $15, which costs more than the admissions ticket at Mission Dolores. But as I’ll share later, it was totally worth it!

Before proceeding with my self-guided tour (or reading the pamphlet for that matter), I had to linger a while to look at all the artifacts and paintings displayed in the Pilgrim Center. I hadn’t even begun my self-guided tour yet but was already flooded with so much history!

And before a comprehensive review of the Mission Museum, here’s a brief history of Mission San José!

History of Mission San José

The Beginnings

Founded on June 11, 1797, Mission San José was the 14th of the 21 Spanish missions established in California. It was founded by Fermín de Francisco Lasuén de Arasqueta, a Basque Franciscan missionary. Born in Vitoria, Spain on June 7, 1736, Fermín Francisco de Lasuén became a Franciscan priest in 1752. Serving as a missionary in Mexico and then in California, he spent the rest of his life in California until his death at Mission San Carlos Borromeo in Carmel-By-The-Sea. As Junipero Serra’s successor as president of the California missions, Lasuén established 9 more missions after Serra’s death.

Mission San José came after Mission Nuestra Señora de la Soledad and before Mission San Juan Bautista (both founded by Fermin Francisco de Lasuen.) What’s interesting about the California missions is that they weren’t established in geographical order. One would assume Mission San José was founded after its closest neighbor, Mission Santa Clara, but it wasn’t.

Ties to Mission Santa Clara

However, Mission Santa Clara, which was founded 20 years earlier, was crucial to Mission San José’s beginnings. It was the Native Americans who had already been baptized at Mission Santa Clara who built Mission San José and became part of the new community in Fremont, area known back then as Oroysom.

According to Francis Florence McCarthy’s The History of Mission San Jose, Mission Santa Clara even sent a gift of “600 cows, 4 teams of oxen, 3 mules, 4 tame horse, 2 bulls, 28 steers and…a flock of 78 sheep, 2 rams, and 20 other sheep.”

And it was Father Magín Catalá of Mission Santa Clara who performed the first baptism at Mission San José, to a Native American woman named Josefa. (To read about Magín Catalá and Mission Santa Clara, click HERE.)

But Why Mission “San José “?

You may wonder as I did: why is the Mission called, “Mission San José” when it’s not even in San Jose? I found out that it’s because the Mission is named after St. Joseph, the stepfather of Jesus and husband of Mary, just as the city of San Jose is. Because St. Joseph is the patron saint of pioneers, many of the early settlements in California were founded in his honor.

So, that’s why: Mission San José and the city of San Jose are both named after St. Joseph. (He also happens to be one of Santa Clara University’s patron saints, along with St. Clare of Assisi and St. Ignatius of Loyola.) This is explained inside the Mission Museum, along with more interesting facts:

The full name of the Mission was “La Mision del Gloriosisimo Patriarch San Jose.” But according to the visitors’ guide, it is now known as “the parish of St. Joseph Catholic Church, Mission San José of the Diocese of Oakland.”

Early Years

During its early years, Mission San José was where Franciscan missionaries taught the Ohlone Native Americans Christianity and Spanish ways of life, including cattle and wheat farming. The very first missionaries arrived at the Mission on June 28, 1797, about 2 weeks after its dedication.

From just 33 Native Americans in 1797, the Native American population in the Mission reached 1,886 by 1831. But the population fell drastically after epidemics; about 80 percent of the Native Americans in the Mission died due to European diseases. The Mission recruited diverse Native American groups to maintain itself (as it was the Native Americans who did all the work at the Mission), and it soon became a hub of different Native American peoples, including the Ohlone; Bay, Coast, and Plains Miwoks; Yokuts; and Delta Yokuts. With its diverse population, Mission San José thrived and became prosperous from all the ranching and farming.

The Native American Perspective

What’s fascinating and heartbreaking at the same time is what the Native Americans experienced. They came in contact with people and animals like horses that they had never seen before. Intrigued and hospitable to the newcomers, they traded goods with them and eventually worked at the Mission during the day while living in their villages. But when diseases killed large numbers of their population and livestock grazing disrupted their livelihood, they had no choice but to live at the Mission, where they were expected to work and participate in religious activities.

What becomes more tragic is that neophyte2 Indians could not leave the Mission without permission once baptized. Even if they were allowed, they had to return no matter what; otherwise, soldiers would be sent to catch them. Their freedoms were further restricted in other ways. They were rebuked and/or punished when they didn’t obey orders, and Priest Pedro de la Cueva confiscated ornaments and other items related to ritual dancing, giving them back only when he allowed a performance. (But the Native Americans at Mission San José fared better than those at Mission Santa Cruz, who were even whipped when they didn’t follow orders!)

And again, Native Americans did all the work at the Mission, from constructing it to farming, weaving, cooking and more.

The work of Franciscan missionaries who risked their lives to spread the Christian faith is incredible. Though there were unexemplary priests, there were those who actually followed Christ and lived sacrificial lives, treating the Native Americans with love. Yet, because the missions were part of Spanish Empire’s goal of subjugating Native Americans, they had inherent elements that reflected its imperial nature.

Accounts from Explorers

Did you know that explorers from Russia set foot in the Bay and its missions? I knew about their explorations in the Arctic and Alaska but I had no idea that they actually traveled all the way down to Fremont! And these explorers wrote and drew about missions like Mission Dolores and Mission San José, along with the Native American inhabitants:

🧭A Russian count named Nicolai Rezanov led an expedition into the San Francisco Bay in 1806 and had a chance to visit Mission San José. German naturalist/physician Georg von Langsdorff was there to write all about it in his book, Voyages and Travels in Various Parts of the World, During the Years 1803, 1804, 1805, 1806, and 1807 (talk about a long title!) Below is his drawing of the dancers he saw at Mission San José in 1806 along with a diorama at the Mission Museum showing dancer figures as depicted by Langsdorff:

HERE is a better photo of Langsdorff’s drawing.

🧭In addition to Rezanov and Langsdorff, there were Otto von Kotzebue and Louis Choris.

Kotzebue visited the Bay Area multiple times during his voyages to find a sea route through the Arctic. Louis Choris was the expedition artist who accompanied him, and many of his drawings are shown throughout the Mission Museum:

To view better photos of the drawings above and for more works by Choris, visit the official Muwekma Ohlone Tribe website at: https://www.muwekma.org/customs-traditions.html

Secularization & Rancho Era

Just like the rest of the California missions, Mission San José was secularized in 1836 after Mexico’s revolution in 1821 ended Spanish colonial rule. And like the rest, it fell into decay. The Mexican Governor appointed administrators to take over the Mission, divided up mission lands into “ranchos” and gave them out to powerful families.

The ecosystem as well as the buildings of what had once been Mission San José deteriorated. And the Native Americans who had lived at the Mission were unable to claim the lands held in trust for them by the Franciscan friars. While some worked at the ranchos and at the San Jose Pueblo and those who recently joined the Mission returned back to their villages, many died of starvation and disease.

To summarize, Mission San José started out as a mission where Franciscan missionaries shared their faith with the Native Americans of the Bay, under the rule and provision of the Spanish Empire. Then the Mexican government took over the Mission, secularized its lands and gave them out to Californio3 families, ushering in the Rancho Era. It experienced even more changes when the Mexican-American War of 1846 broke out. American settlers from the east arrived in large numbers and squatted on the lands of the Californios. Then with America’s victory and discovery of gold in 1848, a record number of immigrants flooded into California.

California Statehood

With California’s statehood in 1850, the Mission’s ecosystem and landscape forever changed. It was used as a store/saloon until the American government returned a small part of the Mission land back to the Catholic Church. And in 1865 under President Lincoln’s leadership, some missions, including Mission San José, were given back to the Catholic Church.

Tragically for the Native Americans, their plight “became nothing short of hell,” with the arrival of the early Anglo pioneers as they faced slavery, disease, liquor, massacre, and genocide (from Jack Holterman’s “The Revolt of Estanislao” in Indian Historian 3.1, p54).

More History: Chief Estanislao

Before visiting Mission San José, I did a quick search online and read that there was this Native American leader named “Estanislao” who led hundreds in a revolt. I couldn’t find much info on Estanislao throughout my visit except for this one-pager that mentioned his name once:

But I think his story deserves more than just a quick mention!

Life of Estanislao

Born in present-day Modesto, CA, Estanislao was called “Cucunuchi” before being baptized as “Estanislao.” Some sources, like A Cross of Thorns by Elias Castillo and Jack Holterman’s “The Revolt of Estanislao,” say that he was born at the Mission with some Spanish ancestry. He was part of the Lakisamni tribe of the Yokuts people and lived on the banks of the Stanislaus River, known back then as “Río de los Laquisimes.”

The Franciscan missionaries invited Estanislao to receive a Christian education at Mission San José, and in 1821, he was baptized at the Mission. While living in Mission San José, he was an “alcade,” or a municipal magistrate appointed to oversee other Native Americans. Various contemporaries wrote about him, pointing out that Estanislao stood out both in his appearance and abilities.

“About six feet tall, a bit more fair in

complexion than usual, a man of athletic physique

with a face well bearded and an air of gallantry on

horseback-such was Estanislao.”From Jack Holterman’s Article, “The Revolt of Estanislao.” 1970.

The Revolt

When Estanislao and other Lacquisamnes were given permission to visit their native homes in the fall of 18284, they decided not to return. Estanislao wrote a letter to Friar Narciso Durán announcing their decision:

“We are rising in revolt… We have no fear of the soldiers, for even now they are very few, mere boys… and not even sharp shooters.”

Estanislao’s message to Durán. From Robert H. Jackson and Edward Castillo’s book, Indians, Franciscans, and Spanish Colonization: The Impact of the Mission System on California Indians.

Leading other baptized Native Americans back to their lands, Estanislao revolted against the Mexican government and the missions. He joined forces with other Native Americans who had also been abused, including those from Mission San Juan Bautista and the notorious Mission Santa Cruz. A Native American leader from Mission Santa Clara named Cipriano and his followers also joined him.

“You will tell our good Father that from now on our real exploits begin. Soon we shall fall upon the very ranches and cornfields… And for the troops, now as always, we have nothing but contempt and defiance!”

Message from Estanislao to Durán, delivered by a neophyte named Macario. From Elias Castillo’s A Cross of Thorns: The Enslavement of California’s Indians by the Spanish Missions.

Surrender & Forgiveness

Though they fought bravely and were able to withstand attacks from the Mexican army multiple times, Estanislao and his followers eventually had to surrender.

On May 31, 1829, Estanislao returned to Mission San José and asked Narciso Durán for forgiveness. Friar Durán forgave Estanislao and his men, petitioning Governor José María de Echeandía to forgive him as well. Durán also charged the commander Ensign Mariano Guadalupe Vallejo with the atrocities he and his men had committed against Native American civilians during their attempts to capture Estanislao. Though there was a hearing ordered by the Governor, only one soldier was charged with the crime of killing a woman and sentenced to just five years of servitude.

With the pardon granted on October 7, 1829, the short-lived revolt by Estanislao came to an end.

Returning to Mission San José, Estanislao taught Yokuts language and culture until his death. Along with the exact details of the final years of his life, the date and cause of his death vary. Some sources write that he passed in 1839 during a malaria epidemic while others state that it was in 1838 due to a smallpox. I also came across a book that said it was in 1832 when he died of smallpox.

Significance of Estanislao’s Story

Local History

I think Estanislao and his story are significant for a number of reasons. First of all, Stanislaus River and County are all named after him. Per Historic Modesto, the battles between Chief Estanislao and the Mexican army took place by the Stanislaus River. Meaning “glorious” in Slavic, Stanislaus is the original for the Spanish name of “Estanislao.” From Stanislaus River, Stanislaus County and other names like Stanislaus National Forest and California State University, Stanislaus followed.

Native American History

Secondly, Estanislao’s revolt shows the plight Native Americans experienced with the arrival of new settlers. As mentioned earlier, they weren’t allowed to leave the missions whenever they wanted. Not only that but they were forced to work and abide to rules enforced on them, being punished if not obeying. And many of these rules being forced upon them went against their old ways of living, including traditional marriage practices. Situations in the missions had become so bad that Native Americans had to take the matters into their own hands. Estanislao’s revolt gives insight to what they had to endure and what they did to protect the loss of their freedom, dignity, and culture.

*It’s important to note that Estanislao and his followers fought to fend off the Mexican army and protect their freedoms. According to the Stanislaus River Archive, there is “no indication in the records that his rebellion against the Mexicans and Spanish ever involved attacking others, just defending his freedom against the attacks aimed against him.” Despite this, there were casualties on both sides. And Native American civilians, including elderly women, were murdered when Commander Vallejo and his men “viciously lash[ed] out at any Indian they found” (Castillo 188).

Not only was there Estanislao’s Revolt at Mission San José and Cipriano’s uprising at Mission Santa Clara, but there were also a host of other rebellions: at Mission Dolores (led by Pomponio in the early 1820s), another one at Mission Santa Clara led by Yozcolo (a Lacquisamne alcalde like Estanislao), and virtually at all the missions. As written by the author Elias Castillo, these Native American rebellions like Estanislao’s revolt are testaments of individuals “willing to sacrifice their lives to try to halt an inhumane system” (190).

Effects of True and False Christianity

Thirdly, it’s a clear example of how true Christian way of living brings different peoples together while false Christian way of living tears society apart. Many Native Americans welcomed the newcomers into their lands, and accepted the Christian faith that the Franciscan missionaries shared and taught. They respected those who truly followed Jesus in their ways of living, including Father Magín Catalá of Mission Santa Clara.

It was when so-called priests forced obedience upon the Native Americans and punished them (with whips!), and when foreigners subjugated and treated them with no dignity that the Native Americans took initiatives to protect themselves. Estanislao’s revolt exemplies the effect of false and true Christianity, from the eruption of conflict to the reconciliation at the end.

It shows that different cultures, nations, and peoples can only become one in truth, love, and forgiveness: in Christ.

Interesting Facts About Mission San José

🌉Mission San José is the only mission on the east side of the San Francisco Bay.

⛪It’s the second largest mission, right after Mission San Luis Rey. (It definitely felt bigger than Mission Dolores and Mission Santa Clara at first glance!)

🐄Mission San José was not only one of the biggest, but also one of the most prosperous. Per the Mission Museum, there were 12,000 cattle, 13,000 sheep and 13,000 horses in 1831. It’s hard to imagine that there were that many livestock at this site once upon a time:

🎟️The Mission San José museum building is the only surviving structure from the original 1809 Mission.

🎼Music played a big role at Mission San José. While Native Americans of the area had their own music and instruments like timbrels, whistles, flutes, and rattles, they were attracted to those brought by the Spanish missionaries. Friar Narciso Durán (the one who forgave and accepted Estanislao back to the Mission) led the way of teaching Spanish and religious music. From 1806 to 1833, he composed music and organized Indian choir, orchestra, and concerts, launching Mission San José’s musical fame throughout California.

The Mission Museum

Now, back to the Mission Museum. Once the convento or sleeping quarters of the Franciscan friars, the Mission Museum is a series of rooms connected by small openings. Each room has a theme like “The Franciscan Journey,” that details the lives of Franciscan missionaries or “The Ohlone Indians: The Indian Way,” that explains everything about the original inhabitants of the area.

Room #2 “Divine Pilgrimage: The Holy Family”

The first room you get to once you enter the museum is the “Divine Pilgrimage: The Holy Family” room.

It’s a white room filled with Biblical paintings and drawings, from a portrayal of Noah’s Ark to series of artworks detailing Jesus’s crucifixion.

I loved seeing all the artworks showing the people and events leading up to Jesus’s resurrection. But as a historian, I personally was disappointed to find that some of them were just replicas, not the original/historical works. For instance, Noah’s Ark on Mount Ararat is a copy of the original oil painting that was acquired by Sotheby’s from the Neger Gallery. And some were obviously recent works created by modern artists, like this artwork:

Nonetheless, the information displayed in the room was organized well and great to view:

I especially enjoyed seeing actually historical artifacts, like this cupboard:

Room #3: “The Franciscan Journey”

The next room titled “The Franciscan Journey” was designed like a Franciscan missionary’s room. Showing an open Bible on a wooden desk, narrow bed, crucifix, and a Franciscan habit (clothing), this room gave a glimpse of what the lives of Franciscan friars looked like:

There were these QR codes you could scan to learn about the objects on display and about the Franciscan missionaries who risked their lives journeying across the globe to share their Christian faith.

Along with portraits of important Franciscan missionaries like Junípero Serra and Fermín Francisco de Lasuén and an entire section on Father Narciso Durán, there was a crucifix called, “The San Damiano Cross” hanging on the wall.

Per the accompanying description, the San Damiano Cross was the cross before which St. Francis of Assisi (founder of the Franciscan order) had prayed to. It was said that in 1206, St. Francis received a vision from Jesus, who instructed him to rebuild the Church. I thought that this crucifix, unlike some of the paintings in the museum, was the actual historical artifact. But I found out afterwards while doing research that it’s not!

The actual crucifix is in the Basilica of Saint Clare in Assisi, Italy today. Besides this confusingly authentic-looking replica at the Mission San José Museum, another replica also hangs inside the church of San Damiano, the site where St. Francis received his commission from God.

The California Missions Room

The fourth room, titled “21 California Missions,” was an entire space dedicated to the 21 California missions. The walls were decorated with illustrations and info on each of the 21 missions:

Plus, there was this neat miniature model of Mission San José:

As I’ll share down below, the above miniature is a very good model of the actual Mission Church.☝️

From the “21 California Missions” room, you can either go to Room 5 or Room 9. I recommend following the order of the rooms and heading to Room 5, as you’ll be heading towards the exit from Room 9.

The Native American Room

The fifth room, titled “The Ohlone Indians: The Indian Way,” was packed with artifacts, drawings, and information all about the Native Americans who lived in the area before the Spanish arrived. I mean, it was literally an explosive display of artifacts! (I hope they were all or at least mostly actually historical.) There was just so much to view that I began to realize why there was an entire building serving as the Mission Museum. And as a history lover, I thought that this room alone made the $15 admission fee worth it!

This diorama in the middle of the room showing the Ohlone Indians living their lives was a nice touch to the exhibit:

I think I even spotted some of the artifacts on display being used by the figures inside the diorama!

Aside from the ancient baby carriers, another interesting artifact were these sticks used in games:

Very similar artifacts were shown inside the one-room museum at Mission Dolores (click HERE to view the blog post). And sure enough, the accompanying note explains that these stick games were played by many different tribes in the Bay Area, including those at Mission Dolores:

I will touch upon this topic more (hopefully in the near future), but I must briefly mention how strikingly similar these stick games look to traditional Korean game sticks called, “yuts.” Maybe all historical games look similar, but I find it fascinating that both Korean yuts and Ohlone sticks have cross markings on them and each stick has both “up” and “down” sides.

Anyways, “The Ohlone Indians: The Indian Way” room was a stellar display of Native American artifacts, with maps, illustrations and explanatory notes everywhere. In fact, it was one of my favorite rooms at the museum!

St. Joseph Room & Chapel of Healing

After “The Ohlone Indians” room, you get to Rooms 6 and 7. They are more religious than historical, catering to Catholics and their respect towards St. Joseph. The sixth room, titled “The Life and Miracles of St. Joseph,” details the life of St. Joseph with paintings and objects while the seventh room is an actual chapel inside the Museum:

During the Gold Rush, this chapel was used as a store until it was remodeled into a chapel in 1950 under the leadership of Reverend John A. Leal. Under the leadership of Pastor Anthony Huong Le, the chapel was renovated and renamed “St. Joseph Chapel of Healing.” I read that this space has been deemed sacred, formally blessed in 2024, and visited by Catholic pilgrims.

Just like the other Catholic chapels I’ve visited, there were these Stations of the Cross5:

After viewing the decorative sanctuary and wall art, I exited the chapel, totally unaware that there was another room inside the chapel! Called “Sacristy and Sacred Vestments,” Room #8 is where you can view sacred vestments and historic items. Don’t forget to check them out when you visit the Chapel of Healing!

Last Rooms (Room #9, #10 & #11)

The remaining rooms of the Mission Museum are titled the following: “The History and People of Mission San José,” “The Making of the Mission San José Church,” and “Mission San José of Today.” They showcase drawings, artifacts, and information about Mission San José during its Rancho Years, the original 1809 construction as well as the destruction and subsequent reconstruction in 1985, and its active role in Fremont today.

The Rancho Period

Among the Rancho Era artifacts, there was the St. Joseph branding iron that marked objects and livestock of the Mission with its logo, “J.”

Check out this wooden livestock branded with the “J”:

Gothic Church & Construction of Replica

After a major earthquake in 1868 destroyed the original 1809 adobe church of Mission San José, a wooden church was built in Gothic style and used until the adobe church could be rebuilt.

When the authentic replica was completed in 1985, the Gothic church was moved to San Mateo after being used for 96 years. Per the St. Joseph Catholic Church website, the replica is “one of the most authentically reconstructed of the California missions,” made with as much of the original materials and building methods as possible.

Vietnamese Americans’ Contributions

One thing that stood out as I walked through the final rooms of the Museum was the role Vietnamese Americans played in Mission San José’s modern history. Along with Pastor Michael Norkett and art conservator Sir Richard Menn, Vietnamese American Huu Van Nguyen participated in the rebuilding of Mission San José. Vietnamese Americans are also among the many who have donated to and volunteered at Mission San José:

And lastly but not least, the past and current pastors at Mission San José are Vietnamese American as well: Fr. Anthony Huong Lé and Fr. Thi Van Hoàng, who became the new pastor this August.

Visiting the Mission San José Church

There was so much to see, read, and take in inside the multi-room museum that I was literally worn out by the time I came back out to the Pilgrim Center. But the real deal, the adobe Mission San José church, remained yet to be explored. After spending hours in the Mission Museum, I finally made my way through the Pilgrim/Visitor Center to the Mission Church.

*You can only access Mission San José from its side entrance, which can be accessed through the Pilgrim/Visitor Center.

Inside the Old Mission

This is the side door and the only entrance to the old Mission Church:

Behind the heavy wooden door lies this beautiful scene inside:

On the left, behind the front entrance door were these relic-like items. There were no accompanying captions or descriptions, but I think they were/are used for religious purposes:

I saw more items stored above the front entrance, but it was inaccessible to the public:

Down the Aisle (Feat. Religious Artworks)

As I made my way down the chapel under brightly-lit chandeliers, there was something to marvel at wherever I turned:

I mean, just look at the intricate details of the hand-painted wall art! 👀

Along with the Stations of the Cross, there were other paintings hung down the chapel, too. I think the top middle painting depicts Joseph, Mary, and baby Jesus and maybe, the rest depict Franciscan missionaries and saints:

But I’m not positive as there were no accompanying captions or explanatory notes.

There were also these sculptures of Christ, St. Joseph and a Franciscan missionary (I’m guessing Junípero Serra):

…and this statue of Christ on one of the side altars (called “Ecce Homo”), which I read is the original from the 1809 adobe church!

Sanctuary

But of course, the highlight of the chapel was the sanctuary.

The altar consisted of a gilded reredo featuring a statue of St. Joseph and Christ on the cross in the middle, accompanied by candles and angels (both with and without bodies). Above was a painting of Jesus, under sculptures of a dove (representing the Holy Spirit) and God the Father.

Historic Sight to Behold

Stepping inside the old Mission Church was such an experience! I so appreciated the fact that the replica church was rebuilt to be as historically accurate as possible, carefully following the Mission’s inventories from the 1830s and 40s and using as much of the original materials and methods as possible. Kudos to the conservator and restoration craftsman Sir Richard Menn and his assistant Huu Van Nguyen! 👏👏👏

The interior of Mission San José was definitely unique from the other mission chapels, with its green, crimson, and yellow palettes, gilded accents, flashy mirrors and crystal chandeliers. It was such a sight to behold; I can’t imagine how stunning it would have been for those living in the 1800s!

Mission Patio Garden/Cemetery

In between the Mission Church and Pilgrim Center/Museum is the Mission Patio Garden. It’s a quick walk from the Mission Church or the Museum; you just have to follow the sign:

The Mission Patio Garden was a small area featuring a running fountain, benches with dedications and a statue of Junípero Serra.

Per a plaque on the ground, the fountain, patio, and garden are “dedicated to the glory of God,” and commemorates the contributions of the “Abel, Donovan, Morgan, and Jelley families.” It was also a historic cemetery where early settlers, World War II heroes, and other individuals were interred. Many others are buried below the Mission church, including many Spaniards and Robert Livermore, whose grave is marked inside the renovated chapel:

More Cemeteries

Even more are buried in the Mission Cemetery, which is the larger cemetery on the other side of Mission San José. It was gated, so I think it’s off limits to the public like the cemetery at Mission Santa Clara.

And there’s also a separate cemetery located about a mile from the Mission where thousands of Ohlones are interred. It’s the historic cemetery that activist Dolores Marine Galvan and Rupert Costo of American Indian Historical Society (AIHS) protected from the construction of a freeway.

It took me about 20 minutes to walk down Washington Blvd. from the Mission Museum to reach the Ohlone Indian Cemetery:

According to online sources, there’s a grave mark that commemorates 4,000 Ohlone Indians buried at the site. I couldn’t see the plaque from the outside, but I did get to see wooden signages (pictured above). There’s also a shopping center right across the street called “Ohlone Village,” which I think is named in their honor:

Final Thoughts

Visiting Mission San José in Fremont was such a treat! Not only did it have an entire building dedicated to its history, a ton of artifacts, a gift shop, and restrooms, but it also had such unique charm. From its iconic white block of a chapel to its beautifully reconstructed interior, Mission San José was a delight to explore.

One thing that I personally found distracting as a history lover was the presence of nonhistorical artifacts and paintings. They made it confusing to know which artifacts were or weren’t historical. I think it’d be helpful if the Museum only displayed real artifacts or if the replicas were clearly marked as “replicas.” This might not be of importance to others, but I found it a shame for replicas to muddy the actual artifacts on display. Because historical artifacts have utmost value and meaning if they are the actual objects used by those in the past!

What I did love were the QR codes and dioramas that enhanced my self-guided tour as well as these arrows that helped me navigate through the museum. Also, “Acknowledgments” posted alongside informational on-pagers were great as they listed out the sources behind the artifacts and information displayed:

Mission San Jose Today

Once where cultures collided, the parish of St. Joseph Catholic Church, Mission San José of the Diocese of Oakland is a historic site of faith and sacrifice, of musicians as well as local legends like Estanislao. Rebuilt and preserved by the talents and contributions of many, its story continues as a place where all gather and unite under Christ.

P.S. Today, five flags fly outside the Pilgrim Center/Mission Museum. They represent the entities that owned/ruled over Mission San José throughout its 228 history:

- Spain (representing Spanish Empire)

- Vatican City (representing the Catholic Church)

- Mexico

- California

- and the U.S.

P.P.S. After the 1868 earthquake, three of Mission Church’s original bells were transferred to the Gothic-style church while the fourth bell was given to a church in Oakland and recast. Today, the Mission Church houses all four of its bells, and they ring on special occasions. 🔔

P.P.P.S. And here are aesthetic photos of Mission San José to wrap up the post!

Footnotes

- “El Camino Real,” which means “The Royal Road” in Spanish, is the 600-mile path connecting California’s 21 Spanish missions. ↩︎

- “Neophyte” is a term for baptized Christian Native Americans. ↩︎

- “Californios” is a term for the Spanish-speaking Catholics who lived in California when the region was under Spain and Mexico (from 17th to 19th centuries). ↩︎

- These restricted visits were called “paseos.” ↩︎

- Also called, “the Way of the Cross,” it’s a series of devotional images showing the final moments of Jesus’s ministry on earth. ↩︎